|

The Battle of Baker's Creek From

MEMOIRS:

Historical and Personal;

By Corporal

Ephraim McDowell Anderson

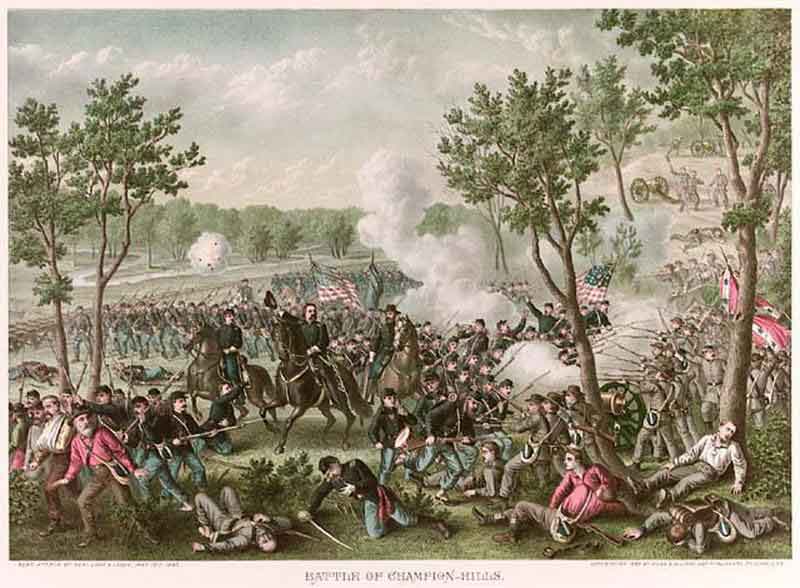

Published by Kurz & Allison, Chicago. Ill, 1887 "Rear Attack by Genl. John A. Logan - May 16th 1863" Library of Congress

On the evening of the fifteenth of May the forces of General Pemberton, in and around Edwards' depot, were marched out on a road leading to Jackson, nearly parallel with the railroad. I cannot be positive in regard to the exact force with us at the time: it was all, or almost entirely, comprised of the three divisions of Loring, Bowen and Stevenson; the last was a large division of three brigades, Georgians, probably seven thousand strong, some of which had never been in battle, and many of the regiments were full. Loring's command was about six thousand, and Bowen's five; there was but little cavalry with us, and the whole force may be estimated at about eighteen thousand men. General Pemberton was in command in person, and moved forward six miles, crossing Coon creek, and took position about ten o'clock, not far from a little stream called Baker's creek. Our division was formed in line with Stevenson's, and on the right, while Loring was a mile back, and rather to our right, on an intersecting road or position exposed to attack; Stevenson's centre rested at the forks of two roads, near the residence of a Mr. Champion, upon whose plantation most of the fighting was done; the name of the owner of this place is not mentioned, however, with certainty. It is not my impression that General Pemberton held any body of troops in reserve; if he did, the force was very small. Although the enemy was near, the night passed, away without any interruption, and in the morning some little change was made in the position of our division, which was moved forward about three-quarters of a mile and formed behind a gentle eminence, crowned with artillery. It commanded a wide scope of cleared land, gradually but slightly sloping, and which extended for a mile in our immediate front, while to the left were woods at the distance of probably four hundred yards. The lines being formed, Colonel Cockrell rode up and down, spoke cheerfully and encouragingly to the men, and told them that he expected the brigade to give a good account of itself during the day. The men were in fine spirits, animated, gay and buoyant, and in good condition for the field. Our company, with Captain Coniff's and Burke's, from the First regiment, were thrown out as a battalion of skirmishers, under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Hubble, of the Third regiment: this was about ten in the morning, and a company of our cavalry, a little over a mile distant in front, was skirmishing with the enemy, who advanced cautiously. Our battalion of skirmishers had proceeded about four hundred yards in advance of the lines, when a Federal battery appeared in sight in the field below, and we were ordered back to the cover of a gully just in front of our guns, which were now in readiness to open. There were ten guns in position here, composed principally of the batteries of Walch, formerly Wade's, and Landis, and I think that one section of Geboe's was with them; all were of tolerably heavy calibre, from twelve to twenty-four pounders. This formidable array of metal opened, firing over our heads, with a tremendous crash upon the enemy before his guns were fairly unlimbered or in battery, at the distance of perhaps a thousand yards. He succeeded, however, in getting into position, and replied in a brisk and spirited manner with six fine Parrot pieces. The most splendid artillery duel followed that I have ever witnessed in open fields, when both parties were in full view; this lasted for thirty minutes, during which time the guns on both sides were handled in the most skilful and scientific manner. Most of the enemy's shells passed over us, and many of them fell in and around the battery, while others struck the ground in our front, and, ricocheting, burst over our heads or beyond, near the guns; the fragments scattered and fell in every direction. Our metal proved too heavy for the enemy; great execution was done, both among men and horses, one of his caissons was struck and blown up, he was finally forced to retreat at a gallop, and left one of his pieces behind, it was thought in a crippled condition and difficult to remove. One of our company, William Sparks, had his head shot off, and four artillerymen were killed at the same piece by the explosion of a shell among them: some were wounded, but not many of the wounds were dangerous. A lull of nearly two hours followed, during which time the Federal artillery did not endeavor to take position again, but a line of infantry was seen to cross the lower extremity of the field, a mile distant, and enter the woods to our left. Our battalion of skirmishers was then thrown forward into the woods, where we maneuvered and waited the approach of the enemy for nearly an hour. At the end of that time, about one o'clock, the roar of artillery was heard a mile to our left, and the ringing reports of heavy sharp-shooting announced that they were coming to close quarters in Stevenson's front; in a few minutes the continued roll of musketry, as it echoed along the lines, indicated that the action had become general at that point. For nearly half an hour we listened to the incessant crash of the small arms and heavy booming of the cannon. The enemy's sharp-shooters were now almost in range of us in front, and a few shots had been exchanged by the left of our line, when an order came to Colonel Rubble, to rally his battalion and follow the brigade, which was moving off to the support of Stevenson. By a blast of the bugle the command was rallied, and the men came up and formed in quick time; the order "forward, double-quick!" was given, and the colonel dashed off at the head of the column, at a gallop; the men followed in full run. Moving rapidly on for the distance of half a mile, we passed General Pemberton and staff standing in the road, almost in the edge of the action. His manner seemed to be somewhat excited; he and his staff were vainly endeavoring to rally some stragglers, who had already left their commands in the fight. Calling out to Colonel Hubble, "What command?" and receiving a prompt reply, he told him to hurry on and join the brigade, as it would be in action in a few minutes. It will readily be seen that after we left our position on the right no troops opposed the enemy there, except Green's brigade, and it was soon ordered to follow ours; from this condition of affairs it is evident that, even if we defeated the Federal force in front of Stevenson, the lines we had left could be thrown without opposition upon our flank, and thus success would perhaps be unavailable. The battalion still moved forward at a double-quick, and soon passed the house of Mr. Champion upon the road, very nearly within the line of the engagement; in the yard was a group of ladies, who cheered the men on, and were singing "Dixie." At sight of this, a novel appearance on the battle-field, the boys shouted zealously, and I could not refrain from hallooing just once, expressive of my admiration for the perfect" abandon" with which these fair creatures gave their hearts to the cause. Large numbers of Stevenson's men now met us, who were falling back in great disorder. These were the same men that afterwards ran out of the intrenchments at Missionary Ridge, and there caused the loss of the battle. About two hundred yards from the house we came upon Landis' battery, in position immediately at the forks of the road, mentioned as being the centre of Stevenson's division, which had now given way "en masse," while the Federals were advancing with triumphant cheers. The battery played vigorously down the road in front, across a small field, and the enemy was in the woods beyond. He had already captured two batteries of Stevenson's division, and his dense and formidable lines came pressing on, blazing with fire. At this point we came up with the brigade, which was formed for action, and took position in the command; a field fence was in our front, which, in an instant, was thrown to the ground.

Cockrell rode down the lines; in one hand he held the reins and a large magnolia flower, while with the other he waved his sword, and gave the order to charge. With a shout of defiance, and with gleaming bayonets and banners pointing to the front, the grey line leaped forward, and moving at quick time across the field, dislodged the enemy with a heavy volley from the edge of the woods, and pressed on. Cheers behind announced the coming of Green's brigade, which soon joined in the action. The fighting now became desperate and bloody; the ground in dispute was a succession of high hills and deep hollows, heavily wooded, called "Champion Hills"—the name sometimes given to the battle. Our lines advanced steadily, though obstinately opposed, and within half a mile we recaptured the artillery lost by Stevenson's division, and captured one of the enemy's batteries. The battle here raged fearfully—one unbroken, deafening roar of musketry was all that could be heard. The opposing lines were so much in the woods and so contiguous, that artillery could not be used. The ground was fought over three times, and, as the wave of battle rolled to and fro, the scene became bloody and terrific—the actors self-reliant and determined; "do or die," seemed to be the feeling of our men, and right manfully and nobly did they stand up to their work. Three times, as the foe was borne back, we were confronted by fresh lines of troops, from which flashed and rolled the long, simultaneous and withering volleys that can only come from battalions just brought into action. Their numbers seemed countless. Recoiling an instant from each furious onslaught of fresh legions, the firm and serried line of our division invariably renewed the attack, and, taking advantage of every part of the ground and of all favorable circumstances and positions, with the practiced eye of soldiers accustomed to the field, we succeeded each time in beating back these new and innumerable squadrons. Once the enemy was driven so far back before fresh forces were brought up, that we were in sight of his ordnance train, which was being turned and driven back under whip. This could be seen where our lines were advanced through the woods to the edge of a large field in front, near which point was a small church or school-house. Though the force in front was vastly superior to ours, yet, if the fortunes of the day had depended upon the issue of the contest between us, as victory thus far was won, it might still have remained upon our side—Grant's centre was undoubtedly pierced. By this time, however, the hostile columns were closing in upon our flank. The troops, which at first were confronted by us, finding nothing to oppose their advance after we marched to support Stevenson, had moved, not only "en fleche," but were immediately threatening our rear; and, at the end of all this hard and desperate fighting—this gallant and triumphant advance, it seemed to become necessary to fall back. Our position was compromised, and the dense gathering lines of the enemy threatened us on three sides. It is true, those in front had been steadily driven, but, conscious of their strength in numbers, and that we were about to be attacked in flank and rear by fresh and superior forces, they had again rallied. In front, on our flank and approaching the rear, were now at least between thirty and forty thousand men—the whole of the centre and one wing of General Grant's army, and I feel confident that the last figure is nearer correct than the first. Our division had fought in this part of the field, unaided and alone, except by the Twelfth Louisiana, a brave regiment. Our number did not exceed five thousand, and we had lost heavily. Under the circumstances, we were ordered to fall back, and this was a necessity. As we came near the edge of the woods, in our retreat, and were about entering the field, a Federal column that had reached our rear, rushed down towards the forks of the road and fired a volley at us, but, coming in range of the battery, the indomitable Landis opened upon it. The thunder of his guns was glorious music to us, and we had the pleasure of seeing the head of the column reel and scatter in the woods, on either side of the road. As we passed on out, he continued to hammer away, and kept it in the shelter of the wood, beyond the clearing. Being the first battery to open the action upon that part of the field, it was the last to close and leave it. Up to this time, I do not think that Loring's division could have been engaged to any extent; if it was, the din of battle and the clash of arms had prevented our hearing his guns; but now, about a mile back upon the road, it was fighting. Whether Loring's entire division shared in this action, I am unable to say; but quite a battle took place at that point, in sight of the road upon which we were retreating, and which led back to Edward's depot. Whatever may have been the extent of the struggle or the number engaged, General Tilghman and his command bore a conspicuous part in it, and that gallant Kentuckian there paid the last debt of the soldier—gave his life to the cause. This brave officer was torn to pieces by a shell, while in the act of sighting one of his guns, which he was in the habit of occasionally doing. This account of his death was received from Captain Ellis, with whom I afterwards became acquainted, and who was then his adjutant-general. He was considered one of Kentucky's brightest ornaments and bravest soldiers. Loring, it was understood, was not disposed to go into Vicks burg. However this may be, he got his division out and Joined Johnson. The manner in which he accomplished this is somewhat remarkable, as he had many obstacles to encounter, and Grant was pressing on at the time with a very strong force. Our division fell back to Black river: Stevenson’s had preceded us. The distance to the bridge was about ten or eleven miles, and we reached that point at nine o'clock in the night. The loss of our division, which had borne the brunt of the battle, was severe, but it was difficult to tell yet the actual loss, as missing parties were constantly coming in. Our brigade was badly cut to pieces. The first regiment was, perhaps, rather the heaviest loser: Captain Fagan's company, of that regiment, which went into the battle with forty muskets and four commissioned officers, came out with seventeen men commanded by the orderly-sergeant: all the officers were killed or wounded. Lieutenant George Bates, of this company, a nephew of the Honorable George Bates, had his arm broken by a minie ball, and walked all the way to Black river from the battle-field—a very remarkable circumstance. The loss of the regiment, though not in proportion quite so great, may yet be imagined or reasonably estimated by Captain Fagan's company. Colonel Hubble, of our battalion was wounded, from the effects of which he afterwards died. A number of the men of our company were killed, wounded and missing, but the officers escaped without injury. Crocket Bower, Fletcher, and one of the young men who had recently joined the company, were known to be killed, besides Sparks, already mentioned, and it was thought by all who saw Charley Hanger struck and left senseless upon the field, that he was dead also; his brother alone entertained faint hopes that he still lived. Of our company, some ten or twelve were wounded and a few others were missing. Pollard, Lannurn and Willis were severely wounded. Among those who were slightly touched, Massey Smith received a scratch from a minie on the cheek. Those who had been killed were good soldiers, and Fletcher and Bower exceedingly clever fellows. The latter was a relative of the lamented General Slack, and a young lawyer by profession: with promising prospects, he had just been admitted to the bar previous to the war. They had given their lives for a Cause they loved, and were now gone to the spirit-land, to join comrades who had already gone before them. Colonel McKinney, who has been mentioned before, fell on this field—a gallant soldier and a brave and intelligent officer. Many of our best officers and men were missed from the different regiments. Their loss and death were deeply felt and mourned by the command long afterwards. The army lay and slept that night inside of our intrenchments, which enclosed a considerable area on the east side of the river. On the same side the enemy was encamped; and it is somewhat singular that intrenchments intended to defend the passage of the bridge or stream towards Vicksburg, should be on the side opposite to that position.

Reference: Anderson, Ephraim McDowell, Memoirs: Historical and Personal; Including the Campaigns of the First Missouri Confederate Brigade, Chapter LXXXI (Eighty-one); Times Printing Co., Saint Louis, 1868. Second Edition with Notes and Foreword by Edwin C. Bearss and Index by Margie Riddle Bearss; The Press of Morningside Bookshop, Dayton, Ohio, 1988.

The Chicago firm of Kurz & Allison is well known for its production of commemorative prints of American historical scenes. Founded in 1880, the firm’s avowed purpose was to design “for large scale establishments of all kinds, and in originating and placing on the market artistic and fancy prints of the most elaborate workmanship.”

|

||

|

| Home | Grant's March | Pemberton's March | Battle of Champion Hill | Order of Battle | Diaries & Accounts | Official Records | | History | Re-enactments | Book Store | Battlefield Tour | Visitors | Copyright (c) James and Rebecca Drake, 1998 - 2009. All Rights Reserved. |