|

The

Search For Fannie Sims Granbury: By Researched

by Rebecca Drake, Mississippi Civil War historian, Mary Eddins Johnson,

When it comes to Civil War history and the wives of famous generals, no one has been more elusive than Fannie Sims Granbury, wife of General Hiram B. Granbury, 7th Texas Infantry. In 1861, Fannie accompanied her husband to war, traveling to Hopkinsville, Kentucky. After the fall of Fort Donelson in February of 1862, Granbury was taken prisoner. The odyssey that followed resulted in Fannie's disappearance, something that has puzzled historians for almost a century and a half. Other than her marriage to H.B. Granberry/Granbury in 1858, little is known of Fannie's earlier life. She was born in Alabama in 1838 and migrated to Waco, Texas, where she met the native Mississippian, Hiram Granberry/Granbury. Hiram had graduated from Oakland College, Rodney, Mississippi, and moved to Texas in the early 1850s. While in Waco, he studied law and was admitted to the Texas bar, and served as chief justice of McLennan County. At the time of their marriage, Hiram was 27 years old and Fannie was 20.1 During the early years of their marriage, nothing was known regarding the personal life of Fannie. After Hiram B. left Waco to join the 7th Texas in Marshall, Fannie went on the move with him. As the troops marched for Tennessee and Kentucky, Fannie took up residence in the home of Stephen E. Trice, Hopkinsville, Kentucky.2 After the capture of many Confederate soldiers at Fort Donelson, Major Granbury petitioned U. S. Grant to give him time (before going to prison) to situate his wife who was staying in Clarksville, Tennessee. The petition was granted. For the first month of prison, Granbury was shuffled from Camp Douglas to Camp Chase. Finally, on March 6, 1862 he was taken to Fort Warren Prison in Boston Harbor, a prison primarily for Confederate officers. While Granbury was at Warren Prison, Fannie lived in Hagerstown, Maryland, at the residence of Mrs. Mary MacGill, wife of Hiram's prison mate, Dr. Charles MacGill. Some historians wrote that she became ill from exposure to the northern climate and died. This was not true. She became ill with cancer, but lived long enough to return south to die.3 The truth of Fannie's illness and Granbury's imprisonment can be found in a document from L. Thomas, Adjutant General, Washington, written to Col. J. Dimick, U. S. Army, Fort Warren, Boston, Massachusetts. The correspondence dated July 29, 1863, read: "The eight or nine prisoners referred to and those who have taken the oath of allegiance will not be sent to Fort Monroe. Parole Major Granbury, of Texas, that he may attend his wife while having a surgical operation performed at Baltimore,…" 4 As it turns out, Fannie never had the surgery at Baltimore Hospital, most likely because her condition, ovarian cancer, was too advanced. Adding to the insight on Fannie's condition are the letters that were written between Dr. Charles MacGill and his wife, Mary MacGill, during the time Fannie was their house guest in Hagerstown These letters reveal personal insight into Fannie's illness and suffering as she waited at the MacGill home for Hiram to be released from prison. Over the course of the years, perhaps stemming as far back as her marriage in 1858, Fannie had begun to experience health problems. After arriving in Hagerstown, the problems became acute and at the urging of Dr. MacGill, she made an appointment with Dr. Smith, a renowned surgeon at the hospital in Baltimore, for an examination and possible surgery. Hiram received an early parole to be with her but apparently instead of receiving treatment in Baltimore, they decided to travel on to Richmond, Virginia, in order to join the other exchange prisoners. At some point, either while in Baltimore or Richmond, Fannie learned the news that she was suffering from inoperable ovarian cancer and had only months to live.5 She was 24 years old at the time. After leaving Richmond, Fannie and Hiram took a train heading for Jackson, Mississippi, the site where the 7th Texas Infantry would meet to reorganize. En route, Hiram dropped Fannie off at Tuscaloosa so she could be cared for by family and friends. Sadly, Hiram rejoined the war efforts while Fannie endured the final days and months of her life. On March 20, 1863, eleven days before their 5th wedding anniversary, Fannie passed away at the age of 25. At the time, Hiram was stationed at Port Hudson, Louisiana, but he hastened to be by her side and then to bury her following her death. The funeral was March 21 from the Providence Infirmary in Mobile but few were present to mourn her departure. Afterwards she was buried in an unmarked grave in Magnolia Cemetery.6 Perhaps, following the war, Hiram had planned to erect a headstone or do something in his wife's memory, but this did not happen. A year following Fannie's death, Brig. Gen. Hiram B. Granbury became one of six Confederate generals killed on the battlefield at Franklin, Tennessee. When Granbury died, all memories of Fannie died with him because they only had each other - no children to perpetuate her memory. Granbury was buried for a short time in the paupers' section of the battlefield. Later, his body was exhumed and reinterred in St. John's Cemetery, Ashland, Tennessee. The general's body remained at this site for 30 years. In 1893, when it became in vogue to honor the heroes killed in the war, Granbury was removed and reinterred in Granbury, Texas, a town named in his honor. In April, 1904, J. H. Doyle, a resident of Granbury, recalled the occasion, "General Granbury's remains were disinterred by my brother, Dr. J. N. Doyle, who was a surgeon in the Army of Northern Virginia, and brought to Granbury by him and reinterred in November, 1893." A Confederate headstone marks his grave. Unlike her husband, Fannie's burial site became more and more obscure with every passing year.7 In June, 2001, after studying documents relating to Fannie Sims Granbury, efforts were made to find her grave. Working with only the fact that she could have died in Columbus (Ohio), Sandusky (Ohio), Baltimore (Maryland), Waco (Texas), or Mobile (Alabama), the search was begun. In January 2002, "Mrs. Fannie Granbury" was found to be listed in the 1863 burial records in Mobile Alabama.8 Having located the city of her burial, a search for Fannie was fully engaged and a professional archivist/genealogist was placed in charge of the research. A death certificate was found in the Sexton Report of Death Records - giving the cause (ovarian cancer) and age (25) at the time of her death. The cemetery lot was found to be one in Magnolia Cemetery, where Fannie had been placed in an unmarked grave 139 years before. The lot had been purchased by someone named Redmond. Presumably, since Fannie was destitute, a friend offered a burial spot.9 Even though it seemed apparent that Mrs. Fannie Granbury was the wife of Gen. H. B. Granbury, further proof was needed to document the finding. Only an obituary or death notice would provide the final and ultimate proof. This was found by researcher, Mary Eddins Johnson, when she began an all-out search for a March 21, 1863, issue of the Mobile Advertiser and Register. Originally, a copy of this newspaper had been in the Mobile Archives but for some reason, the copy was missing. Mary Eddins Johnson proceeded to search in the state of Mississippi, Alabama and Georgia for a copy of the paper. A copy was finally found in the Auburn University Library Archives. The death notice of Mrs. Fannie Granbury was short but exactly enough to identify her as the young wife of Col. H. B. Granbury. "On yesterday, at 11'oclock A. M., Mrs. Fannie Granbury, aged 25 years. Wife of Col. H. B. Granbury, 7th Regiment Texas Infantry. The funeral will take place from the Providence Infirmary, at 3 o'clock P.M. TODAY."10 1 McLennan County, Texas, marriage records, Vol. I (1850-1870) researched by Jane Embrose. 2 Confederate Veteran Magazine, "Mr. Steven E. Trice," Vol. 12, June, 1904. Researched by R. B. Drake. 3 Autograph album of Captain John Tower, 8th Georgia, where H. B. Granbury signed his album in July of 1862. This was researched by Jane Embrose. 4 Correspondence from Records of the Civil War, Vol. 24, researched by James L. Drake. 5 Diagnosis of ovarian cancer found in Mobile death records, researched by Mary Eddins Johnson, Mobile, Alabama. 6 Research of death certificate and burial plot in Mobile, Alabama, Archives by Mary Eddins Johnson. 7 Confederate Veteran Magazine, Vol. 12, April 1904. 8 Researcher Edward J. Lanham found the city where Fannie Sims was buried. 9 March 21, 1863 edition of the Mobile Advertiser and Register, researched by Mary Eddins Johnson. 10 Researched by Mary Eddins Johnson. Regarding the wife of General Granbury. There is absolutely no trace of the Sims family in Tuscaloosa, either before the war or after the war. The only reference to the fact that Fannie was an Alabaman was in her Mobile death record when she gave Tuscaloosa as home. Since there were no children, there was nothing that belonged to either Fannie or Hiram to be perpetuated through the years. When they died, almost everything was lost. There has been no success in finding out anything regarding the Redmond family who purchased the cemetery plot in order to bury Fannie. Fannie Granbury remained the only person buried in the plot until 1900. Today, there is no trace of the original owners and no descendants know of the lot owners. Fannie will probably never be moved to Granbury to be joined with her husband, Hiram. In 2002, after the burial site of Fannie Granbury was discovered in Mobile, Rebecca Drake had a headstone engraved and placed for her in Magnolia Cemetery. A memorial headstone was also placed next to her husband's headstone in Granbury, Texas, where she will be forever remembered as the beloved wife of Brigadier General Hiram B. Granbury. |

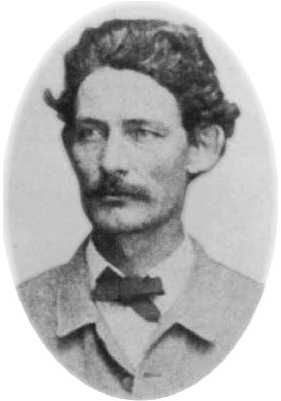

Brigadier General Hiram

B. Granbury

Brigadier General Hiram

B. Granbury