|

Lieut. Col. Leonidas Horney Killed at Champion Hill By Rebecca Blackwell Drake

On February 16, 1866, a funeral procession for Lieut. Col. Leonidas Horney, killed May 16, 1863, during the Battle of Champion Hill, took place in Littleton, Schuyler County, Illinois. A large crowd of citizens came to pay their respects to the fallen hero and to be a part of the patriotic proceedings held posthumously in his honor. A company of Union veterans and a military band led the half-mile long funeral cortege through town and out to the graveyard. The sad beat of the muffled drums was a reminder of the sacrifice that Col. Horney had made for his country. After arriving at the burial site, the soldiers were drawn up in order and, at the word of command, fired three volleys over the grave. The assembly was then dismissed, the grave filled up and all that was mortal of Col. Horney was left to its last long silent sleep. Prior to enlisting in the Union army, Leonidas, his wife Jane and their seven children, lived on a large farm outside Littleton, Schuyler County, Illinois. His parents, Samuel and Emilia Horney, lived nearby. In addition to his role as a farmer, Leonidas was well known as the surveyor of Schuyler County, a trade he learned from his father. When the war broke out in 1861, Leonidas, 44 years old, enlisted in the Union Army. He was over the age of enlistment but his desire to serve his country prevailed. Politically he was opposed to the administration, but he seconded with all his soul its resolution to crush out the traitors, “though it took the last man and the last dollar.” Initially, Leonidas had planned to enlist in his home state of Illinois but, due to the vast number of volunteers already enlisted, he traveled to St. Louis and joined Co. A, 10th Missouri Infantry. In 1862, he was promoted to major and was heavily engaged in the battles of Corinth and Iuka, distinguishing himself by “his fearlessness of danger and great daring.” Prior to the Vicksburg Campaign, he was elected lieutenant colonel of the 10th Missouri. On April 15, 1863, Col. Horney was assigned to the 2nd Brigade, 7th Division of McMcPherson’s XVII Corps. On April 30 – May 1st, when Grant finally executed his amphibious crossing from Disharoons’ plantation on the west bank of the Mississippi River to Bruinsburg Landing near Port Gibson, Horney was a part of the operations but due to a boat collision during the crossing, his regiment arrived too late to engage in the Battle of Port Gibson. After the Union pocketed the victory, McPherson’s corps began marching east, a route which took them through Port Gibson and on to the village of Willow Springs. McPherson made Willow Springs his headquarters but many of the soldiers moved a few miles north to Hankinson’s Ferry, a major crossing over the Big Black River leading into Vicksburg. While relaxing at Hankinson’s Ferry, Horney took the time to write home to his parents:

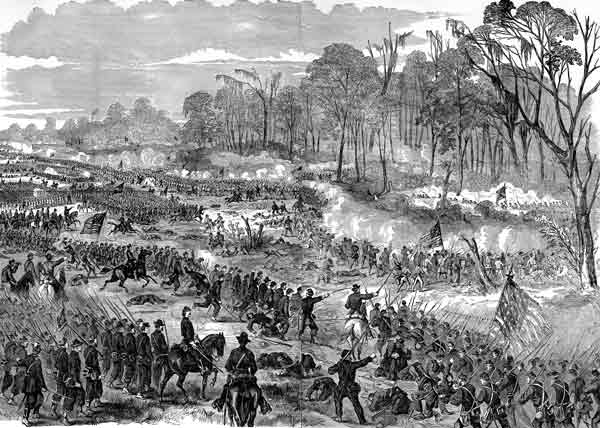

The letter of May 6 would be the last letter Col. Horney would write home. He continued in the campaign, fighting in the battles of Raymond and Jackson. On the morning of May 16, 1863, his regiment marched to a site between Bolton and Edwards known as Champion Hill where he was killed in battle. The story of Horney’s death is best described in his obituary, published in 1866: "On the 16th, after a severe march of twelve miles, through the excessive heat of that region, they were met by an aid-de-camp in the hot haste, and informed that at Champion Hills, some distance ahead, the enemy were pressing our forces hard and unless speedily relieved, would ruinously defeat them. "Though tired, hungry, and thirsty, our gallant boys bounded for war, throwing away their blankets, knapsacks, and everything that impeded their march, arriving just in time to find their comrades out of ammunition and retreating in confusion before the exultant foe. Without a moments delay, they rushed upon the advanced herds of treason, at once the tide is turn back, and the Star Spangled Banner again waves triumphant on the field. In all of this Col. Horney’s voice was heard, and his presence seen, wherever the fight was severest, encouraging his men. "The fight being ended, Col. Horney observing a number of men in federal uniform at a short distance, but uncertain whether friend or foe, rode forward to ascertain. He soon discovered what they were, and turned to order his men forward at this moment a volley was fired upon him, and he fell instantly killed, with three balls in his head. Thus perished in the defence of his country, one of her bravest and most patriotic sons." Approximately three or four weeks after the Battle of Champion Hill, Jane Horney received the letter that the family prayed would never come. A fellow soldier and friend of the colonel penned the letter on May 24th, ten days after the momentous battle.

For three years, Lt. Col. Horney’s remains lay beneath the “large tree” on the Champion Hill battlefield. In 1866, Lt. Col. and Mrs. Sid Champion graciously gave the Horney family permission to disinter their loved ones’ remains. The colonel was finally returning home. Over the years, the Champions befriended many a visitor, north and south, who came to their door asking permission to visit the battlefield and to search for their deceased. During the cold of winter, the remains of Col. Horney left Bolton Station en route to Illinois. On February 16, 1866, Lieut. Col Horney was laid to rest in his beloved town of Littleton where he would be remembered by family and friends. Marilyn Gand, the great-great granddaughter of Col. Horney, commented on the family after the war: “Before the war, Leonidas owned quite a bit of property so, after his death, Jane really had her hands full with 7 children to raise and managing the farm. Fortunately, some of the children were old enough to take on responsibilities, and they did have help from neighbors and other family members. In letters to Jane, Leonidas gave very good advice about the education of his children, what their duties should be, when and what to plant, besides how to handle their finances. Jane must have been a very strong and capable woman. She never remarried and died in 1907 at the age of 83.”

_________________________________________________________

2. The pontoon bridge Horney referenced had been built by the Confederates at Hankinson’s Ferry prior to the battle of Port Gibson. The bridge was used to move the Confederate troops from Vicksburg to Grand Gulf. On the afternoon of May 3, the bridge was captured by the Union army. 3. On May 5, General Grant ordered a scouting expedition on the Warren County side of the Big Black River. The expedition was led by Col. George Boomer. As the men moved northward on the road leading to Vicksburg, they were able to scout enemy territory almost to Redbone Church. After returning, Col. Boomer reported to Grant that the Confederates were on Redbone Ridge, thus aiding Grant in his decision to turn eastward and move toward the Jackson-Vicksburg Railroad. 4. The railroad connecting the capital city of Jackson with the river city of Vicksburg was built 1837-1840. The railroad was originally named the Vicksburg-Jackson Railroad but was later changed to Southern Railroad. The railroad crossing over the Big Black River was located between Bovina and Edwards. 5. The Big Black River, a tributary to the Mississippi River, forms the line which separates Warren County from Claiborne and Hinds Counties. During the Vicksburg Campaign, the Big Black River played a major role for both armies. The railroad bridge near Bovina was burned by the Confederates on May 17, 1863, following their loss at the Big Black. The Yankees built temporary bridges and soon executed the crossing which put them six miles in the rear of Vicksburg. 6. During the battle of Port Gibson, Maj. Gen. John Bowen had a force of 5,500 men. Even with reinforcements, the total number of Confederates south of the Big Black could not have exceeded 10,000. 7. The crossing referred to by Horney was Hankinson’s Ferry, located on the Port Gibson -Vicksburg Road north of Willow Springs. This was the first major crossing of the Big Black after traveling eastward from the mouth of the Mississippi River. 8. While marching east of Port Gibson, the union soldiers passed plantations and foraged for food. They passed Col. Benjamin G. Humphrey’s plantation, and found eight thousand pounds of hidden bacon. The soldiers impaled the pork on their bayonets and continued marching. 9. As the Union army marched into the heart of Mississippi, they destroyed plantation homes, crops and private property. Slaves were told that they were free to leave, so many of them struck out on their own without knowing where they were going or who would feed them. Many of the newly freed slaves were turned into personal servants by Union officers. Others were put to work doing manual labor. The plight of the Negro during this time was a sad episode in American history, many dying of starvation and disease.

Letters edited for clarity by Rebecca B. Drake Sources: Obituary of Lieut. Col. Horney, 1866, Littleton, Indiana; May 6 and May 24, 1863, letters provided by Mrs. Marilyn Gand, great-great granddaughter of Col. Horney; and Parker Hills, Civil War historian and co-author with Edwin C. Bearss of Receding Tide.

| ||||

|

| Home | Grant's March | Pemberton's March | Battle of Champion Hill | Order of Battle | Diaries & Accounts | Official Records | | History | Re-enactments | Book Store | Battlefield Tour | Visitors | Copyright (c) James and Rebecca Drake, 2011. All Rights Reserved. |