|

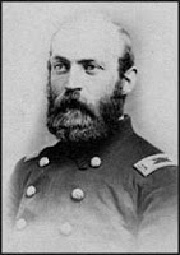

Civil War Diary of General Joseph Stockton From The Vicksburg Campaign, May 1863.

May 10. Left camp on Smith's Plantation early this morning. Marched to Perkin's Landing, on the Mississippi River. Men on half rations; everything reduced to the smallest allowance possible. May 11. Reveille at four o'clock; started on our march after a "hearty cup of coffee." Struck inland and marched around Lake St. Joseph, through one of the most beautiful countries I ever saw; the plantations large and residences elegant; one in particular, Judge Bowie's, was one of the most elegant places in the South; the flower garden eclipsed anything of the kind I ever saw. Most of the men had bouquets stuck in their muskets. My horse had his head decorated with them. This elegant place was in ruins by the time we got there. The house had been burned, as were most of the residences around the lake, and all the cotton gins. Most of the owners had fled and left their houses to the care of the servants. I must say that the officers did what they could to prevent it, and General Ransom halted the brigade and said he would have any of his command severely punished if caught in the act of setting fire to any building, yet while he was talking, flames burst forth from half a dozen houses. Marched eighteen miles. May 12. Started at 5 a.m. Marched to "Hard Times" landing, on the Mississippi, where we immediately embarked on board a transport and were ferried across to Grand Gulf. Visited the fortifications, which were most extensive and almost impregnable; our forces coming up in the rear forced the Rebs to evacuate them. May 13. 72d I11. detailed as rear guard. A large train of supplies and ammunition going out to the armies in advance. Roads terribly dusty -and weather exceedingly hot. Met hundreds of "contrabands" going into Grand Gulf. No one can imagine the picturesque and comic appearance of the negroes, all ages, shapes and sizes. All seemed happy at the idea of being free, but what is to become of them the men can be made soldiers, but women and children must suffer. Encamped in a beautiful grove ; not having tents, we bivouacked in the open air. May 14. Commenced our march at 4 a.m. Marched to the Big Sandy River, where we had quite an exciting time. A courier from the river rode by and reported that Richmond had been taken. There was great enthusiasm among the men. Marched about twenty miles today. May 15. Weather warm and roads dusty. Marched over the battlefield of Port Gibson, where McPherson cleaned the rebels out most effectually. Twenty- two miles today. May 16. Started at four a.m. Reached Raymond by ten o'clock. The churches were full of the wounded rebels and our men, for there had been quite a fight here, as well as at Port Gibson. We had cleaned the rebels out and our men were in the best of spirits. While resting here, heard firing in the distance. Started at quick time ; men were drawn up in line of battle about five miles from Raymond, across a road, but the enemy had gone around us. Orders came to move forward in a hurry. Met some brigades resting on the road, but General Wilson of Grant's staff hurried us forward across fields and arrived at Champion's Hill just as the enemy fled. We were pushed forward to the front and slept on the field of battle. Dead rebels and Union soldiers were lying all around us. The enemy had fled across the Big Black River. Our victory had been complete, captured over two thousand men, seventeen pieces of artillery and a number of battle flags. Marched twenty-five miles today. May 17. Drove the enemy across the Big Black River, capturing quite a number, with artillery; built a bridge, taking the timber from cotton gins and houses in the neighborhood. The Rebs had burned the railroad bridge, as well as the wagon bridge. We were thrown across in advance and thrown out as skirmishers until the division could cross. There was a hard fight at this place, but nothing could withstand the impetuosity of our men; I never saw them in such spirits. Rations short and all are glad to get what they can. It was here an incident occurred which, had it turned out differently, might have affected my position in the army. While at Grand Gulf it was intimated to me by Colonel Wright that there had been an order received from General Grant's headquarters detaining myself, with two companies of the regiment, as provost guard at the headquarters of General Grant. It was entirely unsolicited by myself and unbe- known to me, but Colonel Starring thought I had a hand in it and felt very sore about it. I paid no attention to it as I did not want it, nor would I accept it could I get out of it. I paid no further attention to it until after the battle of Champion's Hill. As we were marching along the road to the front, General Grant and staff came along. General Rawlins, chief of staff, asked me why I had not reported with my companies, as ordered. I told him I had never seen the order and I had no opportunity of reporting until that moment. There was no further time for talking as the road was crowded with troops, and all pressing to the front. That night I saw General Ransom, who was a friend of mine, and asked him to help me out of the detail. He said to come up in the morning to his quarters. I did so, and he gave me a note to General Grant, asking him to relieve me from the detail. I took it, rode to the front where the battle of the Big Black was going on, and found General Grant and staff watering their horses in a pond of muddy water. I presented the note to General Rawlins, who read it and then handed the same to General Grant. He read it and excused me. I asked General Rawlins if I could be of any service : he said to hurry back and tell Ransom to hurry to the front, as there was a sharp fight going on. I did so, reported to Ransom with my instructions, and he marched the men harder than they had ever been marched before, but the victory was won before they got up. This incident I write to show that I would rather stay with my regiment than be on General Grant's staff. May 18. Roads

terribly dusty and weather hot. Marched quick time; water scarce,

rations reduced, consisting of two pieces of hard tack and half rations

of coffee a day since leaving Grand Gulf. Sherman's corps got ahead of

us. Reached our long-looked-for destination at last, the rear of

Vicksburg. We arrived about dusk a mile outside of the rebel

fortifications. Sherman's corps marched to the right of the Jackson

Road, the one on which we entered, their right extending to the

Mississippi River (north of Vicksburg), McPherson's corps coming next,

and Ransom's brigade being in the front, took position on Sherman's

left, and McClernand's corps coming in on another road took position on

McPher- son's left, and at last we had the rebels hemmed in Vicksburg,

the goal of our hopes for months past, the object of so many hard

marches, the rebel stronghold in the West, the only point that kept the

Mississippi River from being free to the North. The 72d 111. was thrown

out as advance guard that night and myself as officer of the guard.

Although completely worn out I did not dare to sleep, but kept moving

from point to point all night. At one time a party of cavalry came

riding along the road on which I had posted some men, and although

dressed in our uniform my men would not let them pass until they had

sent for me. I recognized one of the officers and permitted them to go

through. A large fire was burning in Vicksburg, but we could not

discover what it was. We knew there would be bloody work for the morrow,

as we would have to assault their May 19. The

different corps had only taken such positions yesterday as they could in

the dark, but today troops were constantly being brought forward and

assigned positions as best they could. Our regiment was still in the

front. Skirmishing commenced early in the morning. Company E advancing.

I had charge of the skirmishers. They drove the rebel pickets in and

took an advanced position. They were not strong enough, and I went back

to the regiment and brought forward Company K, Captain Reid. They were

advancing over a hill, when Captain Reid was shot through the wrist. He

was taken to the rear and had his arm amputated that day. He was a brave

man and a surveyor by profession, and should he survive would miss his

arm and hand terribly. Two companies from Logan's Division relieved us

and we rejoined the regiment. General Ransom ordered me to reconnoiter

and see if I could not find a way to join the brigade to Sherman's left

without cutting through the cane brakes, which were as thick as they

could grow. I never had such work in all my life, climbing up and down

ravines, my horse at one time getting so tangled that I was afraid I

would have to leave him through cane, over and under fallen May 20. Skirmishing going on all day, the rebels' position being reconnoitered by our general officers and their staffs. Hot work before us. I climbed a tall tree and could see over their works. They have formidable abattis in front and we will have to charge under every disadvantage. May 21. Skirmishing, as usual. Quite a number of officers were sitting together just before dark eating their supper of coffee and hard tack, when the bugler of the regiment, who was sitting near, was shot through the heart and killed instantly. No one could tell where the shot came from. He was just raising his spoon to his mouth, when he fell over, dead. We buried him that night, performing a soldier's burial, but a number of the officers and men had service over the dead, and we all sang a hymn. Who knows who may be living tomorrow night. May 22, 1863. A day long to be remembered by those who participated in the events I now write about. We all knew we were to assault the rebel works, and that there would be bloody work. The day was a beautiful one, but very warm. We got breakfast early, and shortly word came that the assault would be made at two o'clock promptly, but that we would move at ten o'clock to take our positions. The ground had been reconnoitered as best it could by General Ransom and the field officers of the brigade the night previous. Early in the morning General Ransom and staff took seats near our quarters, where we had a good position, to see the rebel works. We talked and chatted, and Colonel Wright had a splendid field glass, and Ransom remarked jocosely: "Colonel, if you are killed I want you to leave that glass to me." "All right," said he, but I remarked : "Stop, Colonel, you forget you left that to your boy when you made your will at Memphis." "That is so," replied Wright. Poor fellow, a few hours after- wards he was carried off the field badly wounded. I climbed a large tree to get as good a view as possible, and reported to Ransom that they had no interior works but a single line of fortification. When 10 o'clock came we fell into line and the regiment counted; we numbered four hundred men. At the word "forward" we started in two ranks down the ravine and commenced to climb up the ascent on the other side. Company A in the advance. It was hard work climbing over and under the trees that the Rebs had cut down to impede our advance. We got within thirty yards of their works, creeping on our hands and knees, when four of Company A were shot, two killed instantly. Corporal Nelson and Private Harding, and Corporal Heberlin and Private Kassill mortally wounded; both died at night four as good men as ever drew breath. We were ordered to change our position, and in doing so a Lieutenant left his sword near the spot where the men were killed. I climbed up and got it for him and sent it to him with my compliments; got into our new position and waited for the word. Generals Giles A Smith and Ransom and other officers got together in the ravine and arranged their watches and how they should start. At last, at two o'clock promptly, the word came to "go." Up we started and rushed ahead with a yell, and were greeted with a most wondrous volley. Our colors were planted about fifteen feet from the ditch, but we could not go forward, the fire was too severe, men could not live ; we laid down and only the wounded fell back, while shot and shell from the right and left and our own batteries in the rear, whose shell fell short, did terrific work. Men fell "like leaves in wintry weather." Colonel Wright was carried off the field terribly wounded. Colonel Starring incapacitated by a sunstroke, when the command of the regiment fell upon myself. General Ransom tried to have us go forward, but we could not do it. At last he gave the word to get back into the ravine, which we did, marching off as quietly as on dress parade, carrying the wounded with us, but leaving the dead. We reformed and then waited for further command, as we expected to make another charge, but thank heaven, orders came only to move up to our former position and hold the ground, which we did, and remained until midnight, when we were ordered back to our camp. What a night! Such a night I never spent before. About dusk there was quite a panic, but fortunately it was checked. The stench was horrible. Many of the men from being completely worn out fell asleep, but I could not close my eyes. None knew but what the Rebs might sally out, but they were only too glad, I guess, to stay where they were, having repulsed us. I cannot go into the details of the charge, but it was horrible, bloody work. Our loss in twenty minutes was one hundred and ten killed and wounded. Such was the 22d of May, 1863. May 23. Busy all day in getting details of yesterday's work so as to report to brigade headquarters our losses, etc. Part of the regiment was detailed to build fortifications. May 24. Our position being too much exposed, orders came to move back into the ravine back of our present location, but we are now inside of five hundred yards' distance of the rebel works. May 25. The stench from the bodies lying unburied on the battlefield becoming so great a flag of truce from the enemy made its appearance and permission given to bury our dead. I did not go on the field, having no relish for such sights. May 26. We have now commenced to make a regular siege. We have the rebels cooped in and intend keeping them there. Pickets are thrown out in front pretty well up to their works, and all day long the firing is steady, but without much damage. May 27. Everything quiet. Visited the hospitals to see our wounded boys; some may get over it, but I fear many will die. May 28. Heavy cannonading all along the whole line. The Rebs reply but feebly; they will not have much chance to rest. May 29. Worked all night on a fort for Major Powell's Battery; as the position is too much exposed for work in day time, it has to be done at night. May 30. Tremendous cannonading early this morning. I have never heard anything to equal it. It seems to be Grant's tactics to keep the Rebs busy all the time. There must have been over a hundred guns firing at once. May 31. As corps officer of the day, I was up all night. Visited the different posts where men had been stationed as pickets. Made some suggestions to headquarters which were complied with.

Submitted by Don Sides, Coffeeville, Mississippi |

|

| Home | Grant's March | Pemberton's March | Battle of Champion Hill | Order of Battle | Diaries & Accounts | Official Records | | History | Re-enactments | Book Store | Battlefield Tour | Visitors | Copyright (c) James and Rebecca Drake, 2011. All Rights Reserved. |

May

9. Received orders to move tomorrow. Our camp life at Smith's Plantation

has been as pleasant as we could wish. Our time was spent in battalion

and company drills and dress parades. Part of the time we were engaged

in building bridges across the bayou for troops to cross on which would

shorten the distance materially between Milliken's Bend and Grand Gulf,

or Carthage, which is opposite. One of the wonders of the day was our

men bringing a small steamboat through the bayou from the Mississippi

with commissary stores and ammunition, something I believe was never

done before. This plantation is a large sugar and cotton plantation and

has several large sugar works and cotton gins on it. It is a valuable

one, worth before the war many hundreds of thousands of dollars, but as

the darkies have all left, there is no saying what it is worth today. I

enjoy the morning and evening walks, as the weather then is delightful.

I saw quite a number of acquaintances pass on their way to the front.

Among them Batteries A and B, Chicago Light Artillery. We have heard of

the battles in the front and that our armies have been victorious. One

day quite a number of rebel prisoners passed to the rear. Our orders are

to move in as light marching order as possible. I take nothing but what

my saddlebags will hold, namely, a change of underclothing and tooth

brush and comb. Captain James, with two companies, C and I, have been

detailed some seven miles from the main camp to guard a bridge over a

bayou. I rode down to see them and found them contented and happy,

indulging in blackberries to their hearts' content. I enjoyed them

myself. We heard the guns at the attack on Grand Gulf, which was a

strongly fortified place, and which defied the gun-boats. It was taken

by troops crossing below and forcing their works. Companies C and I

returned to the regiment last night.

May

9. Received orders to move tomorrow. Our camp life at Smith's Plantation

has been as pleasant as we could wish. Our time was spent in battalion

and company drills and dress parades. Part of the time we were engaged

in building bridges across the bayou for troops to cross on which would

shorten the distance materially between Milliken's Bend and Grand Gulf,

or Carthage, which is opposite. One of the wonders of the day was our

men bringing a small steamboat through the bayou from the Mississippi

with commissary stores and ammunition, something I believe was never

done before. This plantation is a large sugar and cotton plantation and

has several large sugar works and cotton gins on it. It is a valuable

one, worth before the war many hundreds of thousands of dollars, but as

the darkies have all left, there is no saying what it is worth today. I

enjoy the morning and evening walks, as the weather then is delightful.

I saw quite a number of acquaintances pass on their way to the front.

Among them Batteries A and B, Chicago Light Artillery. We have heard of

the battles in the front and that our armies have been victorious. One

day quite a number of rebel prisoners passed to the rear. Our orders are

to move in as light marching order as possible. I take nothing but what

my saddlebags will hold, namely, a change of underclothing and tooth

brush and comb. Captain James, with two companies, C and I, have been

detailed some seven miles from the main camp to guard a bridge over a

bayou. I rode down to see them and found them contented and happy,

indulging in blackberries to their hearts' content. I enjoyed them

myself. We heard the guns at the attack on Grand Gulf, which was a

strongly fortified place, and which defied the gun-boats. It was taken

by troops crossing below and forcing their works. Companies C and I

returned to the regiment last night.